(As promised, Chapter Two of The Butterfly Crest follows. Sorry for the short preamble, but I’m doing what most other authors say you shouldn’t do—obsessing over what I’ve already written. There’s a consensus out there that says you should write, freely, first and worry about perfection later. While I agree with that, the problem I have is that I can’t move forward unless I’m somewhat satisfied with what I’ve written before. I’m not striving for perfection that first time around, but if I don’t get the feel I want out of what I’ve written, I can’t ease into that next scene. I think it’s just the way my brain works. Hopefully, today’s journey will ultimately lead me to a festival scene I’ve been dying to write. If you haven’t read the Synopsis, Prologue or Chapter One of The Butterfly Crest, please do so before reading Chapter Two. Happy reading!)

CHAPTER TWO

The rest of Elena’s week was just as disastrous. Ms. Callas made Elena miserable at work, the few hours of peace Elena normally had at home were slowly being swallowed up by extra work Ms. Callas was having her do, and, it didn’t matter how hard Elena tried, Ms. Callas was never satisfied. The way she expressed her dissatisfaction, in this cold and deceptively passive way, left Elena feeling inadequate, an emotion she was not comfortable with.

To be fair, even without Ms. Callas’ special brand of torment, Elena wasn’t happy. Somehow, between the demands of her career and “living the dream,” discontent had slowly taken root. Elena loved the practice of law. She had wanted to be a lawyer for as long as she could remember—every pet she had during her childhood she had named Cicero—but the reality of law, the business of it, was not something Elena had anticipated or been prepared for. She had been so idealistic about her career that it had left little to no room for the pragmatic aspects of its practice, where quantity was more important than quality; a truth Elena couldn’t reconcile.

This had been her frame of mind for months. Even so, Elena continued to get up every morning to go to a job she didn’t enjoy. She wanted to believe she did so out of a sense of duty or honor, but it had more to do with pride. She refused to be defeated, and so she struggled not to let the discontent consume her. Fortunate for her, she was temperate by nature.

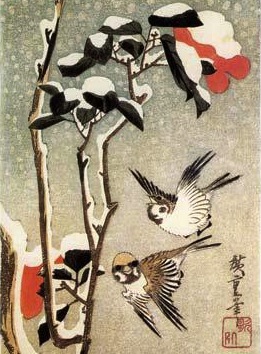

Living in Japan during the first years of her life, and the devastating loss of her parents, had left an indelible mark. Ritual, privacy, modesty, honor and decorum; these things were incredibly important to Elena. Most of all, she was not the kind of woman to wear her emotions on her sleeve. With her, the adage was true—still waters ran deep. And so Elena continued on her path, trying to find the right balance in her life, and hoping she would soon find it.

Thinking it might lessen her unhappiness Elena focused the few work-free hours of her week on doing things that made her happy. On Wednesday, for instance, she visited the New Orleans Museum of Art during her lunch hour, and ran in City Park after work. There was something sacred about walking through the stone halls of the museum, a profound sense of calm, and finding peace beneath the shade of a giant oak tree at the end of her run. On Thursday evening, Elena dined with Cataline.

It was spring, Elena’s favorite time of year in New Orleans, and one that traditionally brought with it evenings spent outside. Since her earliest memories, April was a time for eating in Cataline’s garden, surrounded by blooming hydrangea bushes, the gurgle of a fountain and a continuous stream of birdsong from the trees. Thursday evening was no exception.

“So, tell me about your love life.”

Cataline made her request without any preamble, a teasing smile brightening her face as she set down a plate of roasted brussels sprouts on the table. It was a surprise she hadn’t asked the question before; questions about Elena’s love life were usually the first thing out of Cataline’s mouth, and Elena had arrived an hour and a half before to help with dinner.

“Nothing to tell, really.” Elena made a face and then took a sip from her drink. The food was spread out between them on the patio table, and each held a cocktail in her hand. Elena speared a brussels sprout and chewed on it quietly, while Cataline stared at her across the table.

Cataline was the opposite of Elena. Where Elena was reserved, Cataline was loud and full of life. The daughter of a French pianist and a Spanish cook, Cataline grew up in New Orleans and was childhood friends with Elena’s mother, and, like her, was also an artist. Elena liked to think of her as hippie chic. She had long, curly chestnut brown hair with deep amber highlights, light olive skin, deep-set hazel eyes, and cheekbones to die for.

“Nothing to tell? Is that your story, really?” Cataline stared at Elena with a perfectly arched brow, and downed half of her cocktail in one swallow. “A girl as beautiful as you and no love story to tell. Elena, you’re too serious for your own good. You need to put yourself out there. Every girl needs a good love story, and the love affair with your shoes doesn’t count. Although I can see how red-soled shoes could get any girl’s heart fluttering.”

Cataline’s smile was warm, and as comforting as the summer sun. Elena wished she could smile with that kind of confidence. When she was younger, all Elena wanted to be was like Cataline. Tall, lithe, almost ethereal looking, Cataline was uninhibited and vibrant, something all together different than Elena and the more reserved culture she had grown up in as a child. When Elena had first arrived in New Orleans after her parent’s death, she was floored by the contrast. Cataline wore every emotion on her sleeve, and never kept anything to herself. She was full of joy and she lived every second to the fullest, without reservations.

“You know I splurge on very little,” Elena replied to Cataline’s earlier remark. “I can at least have one weakness,” and red-soled heels were it.

Although Elena’s parents had left her a trust fund with enough money to see her through her childhood and a decent part of her adult life, she did not spend it frivolously. She lived as modestly as her profession allowed, and it was important for her to have savings just in case the worst were to happen to her or Cataline. Cataline didn’t have anyone taking care of her—she was a divorcée—and raising a child had not exactly been economical. Cataline had inherited a house in the Garden District from her parents—an old Greek Revival that was as much a part of Cataline as Cataline’s buoyant personality—and she and Elena had lived in it since Elena’s parents died, but the house was beginning to show its years and if something were to happen to them, they would only have a deteriorating house, and Elena’s dwindling trust, to fall back on.

“I did run into a handsome guy the other day at work, literally,” Elena added, and then recounted for Cataline the story of her encounter with the blonde-haired man. Elena told her story quietly, as they ate, the crisp spring air growing cooler around them as night settled over the small garden. Halfway through, Cataline ran inside to grab a cardigan but the cooler air didn’t bother Elena, although she had to admit it felt colder than it should have.

“And you didn’t even get his name?” Cataline chided her in the end, resting her chin on her hand and giving Elena a half smile; she had topped off her drink only moments before. “That’s what I’m talking about, Elena. You need to take a few risks. Live a little. You should have ran after him and asked for his number or his Facebook name. Isn’t that what you kids do today?”

“I don’t have a Facebook account, Cataline.” Elena tried not to roll her eyes. Instead, she took another sip from her cocktail. “And what was I supposed to do? He was really rude about it. He didn’t offer to help me pick up the papers, and he sure as hell didn’t apologize; not that it was his fault, but it would have been the gentleman-like thing to do. He didn’t even speak. He stared at me like I was a fly in his drink and then walked away.” Now that she thought about it, the incident made Elena angry. The man hadn’t been civil at all.

“He sounds handsome, though.”

Cataline’s voice took on a dreamy lightness when she said it, and Elena couldn’t help but laugh. As Cataline reached for her drink something moved in the air above her shoulder.

Elena leaned forward to see a small, pale blue butterfly fluttering in the air, which she somehow hadn’t noticed before. “Of course, in your school of thinking good looks cures everything,” Elena replied, then shook her head and continued to eat her dinner. By the time she looked up from her plate, the butterfly had gone.

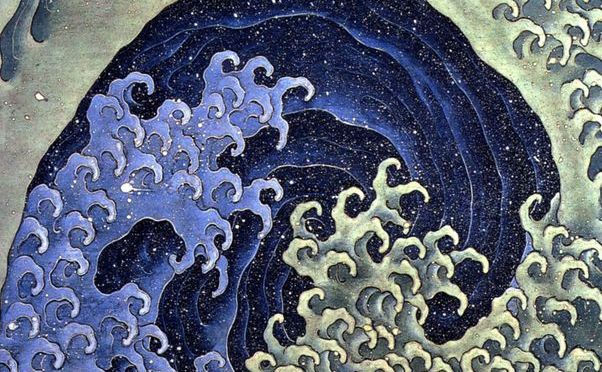

Before Cataline could pick up on the conversation, Elena decided to change the subject to something less annoying; she didn’t want to think about that man or her work. Cataline was obsessed with art, and so for the rest of the meal Elena distracted her with a discussion on the latest art exhibit at the New Orleans Museum of Art, an exhibit on Zen art from Japan. After dinner, Elena helped Cataline clean, agreed to meet her Saturday for lunch at Café Degas—their favorite restaurant—and left before Cataline recalled their prior topic of conversation.

Continue reading On Cataline’s garden, Livia Callas, and the appeal of a finely dressed man

I’ve been thinking a lot about beginnings lately. My days are full of beginnings.

I’ve been thinking a lot about beginnings lately. My days are full of beginnings.

From

From

What I remember most about a book is where it has taken me, emotionally and metaphysically.

What I remember most about a book is where it has taken me, emotionally and metaphysically.

As a writer, you’ll come across these moments (big or small) when you suddenly find yourself thinking it was all for naught, and every nerve in your body is screaming for you to tear it all down and start over again. I’m not talking about the usual artistic dissatisfaction—that’s normal; I’m talking about a sudden shift in perspective where what you had once considered brilliant now seems insipid and forced.

As a writer, you’ll come across these moments (big or small) when you suddenly find yourself thinking it was all for naught, and every nerve in your body is screaming for you to tear it all down and start over again. I’m not talking about the usual artistic dissatisfaction—that’s normal; I’m talking about a sudden shift in perspective where what you had once considered brilliant now seems insipid and forced.

There are days as a writer when you wake up empty. Inspiration eludes you. You may have a temperamental muse. You may find yourself up against a deadline (self-imposed or otherwise). Your mind may be mush because you stayed up working until 3 a.m. the night before. Whatever the reason, the page remains blank.

There are days as a writer when you wake up empty. Inspiration eludes you. You may have a temperamental muse. You may find yourself up against a deadline (self-imposed or otherwise). Your mind may be mush because you stayed up working until 3 a.m. the night before. Whatever the reason, the page remains blank.